We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience. If you continue to browse, you accept the use of cookies on our site. See our cookies policy for more information.

Hidden Christians the missionaries encountered and their revival

What was necessary in order to retrain the descendants of the Christians left in Japan with the correct doctrine? The business of printing catechetical books and so on, the fostering of Japanese priests, deepening of faith, and production of Japanese language hymns to bind together the community of the faithful in one heart. After the Discovery of the Hidden Christians, how did the missionaries act upon the instant that the faith passed down through the ancestors of the Hidden Christians changed? In this part we follow the missionaries as they unceasingly exerted their efforts on behalf of the faithful when they recommenced their work in Japan.

The secret publications of Fr. De Rotz, a revolutionary who loved his fellow men

Ever since the Discovery of the Hidden Christians at Oura Cathedral, the Christians who had at various locations organized themselves into underground faith-based communities called “kumi” and continued to protect the faith, revealed their own version of the Christian faith. Bishop Petitjean and the other Meiji period missionaries dispatched to Japan to once more propagate the faith gently welcomed the Japanese Christians into the church, retrained them in the correct Catholic doctrine, and made every possible effort to enable them to lead new lives of faith. In order to achieve all this, Bishop Petitjean placed an emphasis on the need for catechisms , and headed back to Europe in 1868, returning in the company of Father Marc Marie De Rotz, a priest who also had knowledge of printing technology. And the first job for Fr. De Rotz, who arrived in the midst of a Japan where Christianity was still officially prohibited, was the secret printing of catechisms and other publications in the printing office that had been established at Oura Cathedral.

In the publications that were produced at this time a great deal of effort and ingenuity was employed to ensure that the teachings of the missionaries who had returned to Japan demonstrated that they were the same as the teachings that the ancestors of the Christians had passed down prior to the prohibition of Christianity. For example, in the liturgical calendar that was the first lithographic publication in Japan, in the 1868 Table of Feasts considerable attention was paid to using many Portuguese words for the Christian terminology, as in the Bastian Calendar handed down by the Hidden Christians, and thereby not confusing the faithful. The Liturgy of the Hours , which was the next publication, consisted of a simple text compiled from the verbal transmission of the Hidden Christians in Nagasaki and Sotome under the prohibition, which in turn derived from an old translation once completed by a Jesuit priest. This is the lithographic “Petitjean edition” printed under the guidance of Fr. de Rotz. The Petitjean edition was distributed to the faithful and became permeated among them instead of the “Kirishitan edition” and the orasho that had been passed down among them during the years of prohibition. Up until the time when he was sent to serve alone in the Sotome region in 1879, Fr. de Rotz was involved in the secret publication of 30 lithographic and six letterpress printed volumes.

In this part we will introduce the recommencement of the evangelizing by the missionaries, men who just like Fr. de Rotz - the priest who was active in areas as wide as printing, church construction and welfare – left their home countries and exerted every ounce of their energy for the sake of the faithful who were living in impoverished and isolated islands far across the seas.

COLUMN1 Father De Rotz Memorial Hall

◆Father De Rotz Memorial Hall

Fr. de Rotz, was a missionary born into a family of noble Normandy descent in the northern France village of Vaux-sur-Aure. Fr. de Rotz, who witnessed the wretched conditions of the people in Sotome after taking up his post in Japan, felt that rather than dedicating himself to saving souls he first of all had to do something to save the people themselves. Not hesitating to pour into this work the massive financial inheritance that had been left by his father, he implemented many charitable projects in order to save as many people as possible from poverty, and instructed them in techniques to help them live. In the Memorial Hall, which is housed in the former sardine net factory that he designed and built in 1885, visitors can see many exhibits not only of a religious nature but also technical equipment, carpentry and plastering tools, equipment for making somen noodles and macaroni, and gain a real sense of the tremendous work achieved by Fr. de Rotz.

Let’s take a close look at one of Fr. de Rotz’s great achievements, “the Woodblock Prints of Fr. de Rotz,” created in or around 1875. In order to explain the Christian doctrine in an easily understood manner and to serve as a visual tool for the missionaries, Fr. de Rotz asked a Japanese artist to create ten hand-colored woodblock prints in the manner of the times. It is unknown who the artist or the wood engraver were. The prints have been designated by Nagasaki Prefecture as Tangible Cultural Properties and include the large 128cm x 68cm hand -colored woodblock print depicting the “Salvation of the Soul in Purgatory,” images of saints, and the “Death of a Good Man .” The ten woodblock prints are currently preserved in Oura Cathedral, but there is a total of 86 such prints; versions of a different but similar design, spread across Dozaki Church in Goto City , Oe Church in Amakusa City, and other churches and museums in Kyushu. It is thought that the locations of these prints coincide with the areas of activities by missionaries dispatched by the Roman Curia to recommence the propagation of Christianity in Japan. This fact speaks of how greatly the Woodblock Prints of Fr. de Rotz were used all over Kyushu while the propagation of the Christianity was recommenced.

Secrets behind the creation of Japanese hymns

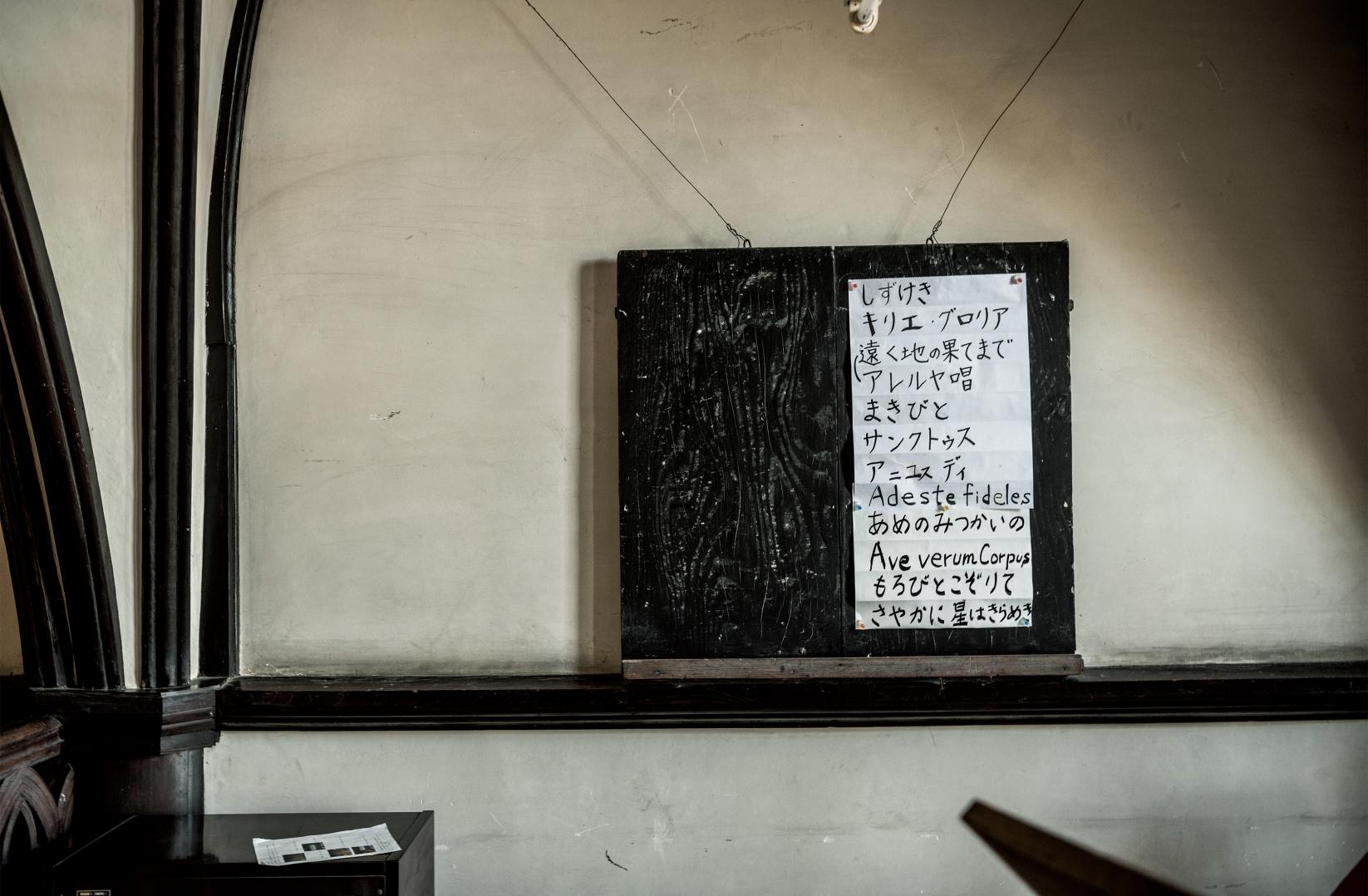

Singing plays an important role in the Christian Mass. It is said that singing is an expression of praise, love and faith, and by singing out loud the feelings of people are induced, faith deepened, and the hearts of the community become united into one. During the recommencement of the propagation of the Christian faith one of the things that the first missionaries dispatched to Japan did was produce “Japanese hymns.”

After the Discovery of the Hidden Christians, the orasho that the Hidden Christians had passed down for generations did not become conventional hymns at the Masses celebrated by Bishop Petitjean. However, the missionaries who felt that it was difficult for the Japanese Christians to sing hymns in the Western musical scale to which they were unaccustomed, are said to have chanted in verbal recitations unaccompanied by music in order to correctly transmit conventional hymns. The collections of hymns compiled at the start of the Meiji were printed in 18 versions. The “Christian Songs” printed at Oura Cathedral by Bishop Petitjean in 1879 as a supplement to the Prayer and Doctrine Book was the first collection of hymns since the Discovery of the Hidden Christians. This translation into Japanese of a collection of Gregorian chants and French hymns was written in a way that continued the tradition of the orasho by including Nagasaki dialect in order to protect the words that the Hidden Christians had handed down over the years.

After the Discovery of the Hidden Christians, despite the huge obstacle of the language barrier between the priests trying to recommence the propagation of the faith and the Japanese Christians, the priests did their best to remain close to the faithful, and it is from this that the Japanese hymns arose. It was surely a quite extraordinary efforts on the part of the priests.

Construction of a proper theological school and the start of doctrinal education

It is said that the Woodblock Prints of Fr. de Rotz were printed at the theological school connected to Oura Cathedral, and the construction of the theological school itself was also the work of Fr. de Rotz. Equipped with a knowledge of the architectural field, before going to serve alone in the Sotome region in 1875 Fr. de Rotz was tasked by Bishop Petitjean with the design and building of the Nagasaki Catholic Divinity School (generally known as the “Latin Seminary”) that was planned to be built next to Oura Cathedral. In October 1877 the first fully-fledged piece of architecture in Japan created by Fr. de Rotz opened as a theological school for the fostering of Japanese priests.

In December 1880 under the tutelage of the first principal of the school, Fr. Jules Renaut, the first three Japanese priests were ordained – Tatsuemon Fukahori, Gentaro Takaki and Hidenoshin Ariyasu – and the fervent hopes of Bishop Petitjean were finally realized. Oura Cathedral was packed with 3,000 Christians wishing to celebrate this occasion, and it is said that Bishop Petitjean sent a message recounting this sense of joy to the headquarters of the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris.

COLUMN2 The former Latin Seminary

◆The former Latin Seminary (the former Nagasaki Kokyo Theological School)

The 20-meter-wide building is a sturdy piece of Western-style architecture, constructed of wood

and bricks over three floors and a basement. The building is unique in that the walls are built up with brick although the frame itself is wooden; the brickwork employs thin red bricks produced in Nagasaki and known as “konnyaku renga,” while the jointing work employs the local Amakawa mixed soil . The louvered windows use transparent glass and while Western architectural techniques were copiously introduced the special feature of the building is its simple and practical design, typical of Fr. de Rotz himself. Until the increasing number of students led to the construction of the school building in Urakami, the Latin Seminary served as both a school and dormitory, and was subsequently used as the Bishop’s residence and meeting rooms.

What appears to be a design sketch of the building drawn by Fr. de Rotz was discovered in the Sotome region’s Shitsu Church. It is a National Important Cultural Property.

The priests who dealt with both “revival” and “hiding”

During the period of the Hidden Christians, it is said that it was the “Bastian Tradition ” passed down through their ancestors that supported the Christians who secretly kept their faith. The missionaries who actually appeared before the Hidden Christians seven generations later were met with different reactions in the places where the Bastian Tradition remained, and in the places where it had not been handed down.

In the regions where the Bastian Tradition had not been handed down, the people who had continued to protect their form of faith as underground organizations had no recognition themselves that they were “Christians,” and thus felt a sense of unease when churches were built in their villages. And without converting they continued to pursue the form of Christian faith that had been passed down to them by their ancestors. They rejected the path of revival, and while placing Buddhist statues on the Shinto altars in their homes they worshipped statuettes of Christ and the Virgin Mary kept out of sight in closets (“closet altars”), and continued to follow the faith in the form passed down by generations of their ancestors. These were the so-called “Hanare Kirishitan” (Separated Christians) . The main villages that until recently had maintained this form of the faith included the former Sotome-cho districts of Kurosaki and Shitsu, and the Goto Islands’ Fukue Island, Nakadori Island, Hirado Island, Narus Island and Ikitsuki Island.

The “prejudice problem” obstructing the revival

Furthermore, three of the four “Bastian prophecies” pronounced on his martyrdom by y the Japanese evangelist Bastian, and passed down in the Sotome region, came true one after another – the first that for the space of r seven generations the children would be regarded as Christians; the second that confessors would arrive in black ships; and the third that a time would come when the hidden Christians would be able to openly sing Christian hymns . However, with regard to the fourth prophecy - that when Christians met non-believers on the road, the non-believers would give way to them – a deeply rooted problem that had built up over the long years of hiding the faith came into play.

The 1878 annual report of the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris recorded that the largest factor in the refusal of the former Christians to return to the Church was “the fear of persecution.” In the background to the fact that some people did not return to the Church even after the Discovery of the Hidden Christians and the lifting of the prohibition of Christianity in the early Meiji period onwards lies the “prejudice problem,” which in addition to the wariness of persecution for announcing their faith, arose from the way they lived in tiny villages. On the Goto Islands where Christians from the Sotome region settled in particular, there was often no contact even with the people in the neighboring villages, and there were differences in dialect too. Furthermore, Christians could also be recognized by their appearance, the result of living in extreme poverty. The Hidden Christians were described as “black” (the non-Christians as “white”) and “non-Buddhists.” Stories remain that from 1874, when ordinary people started to be allowed to adopt surnames, in a sign of contempt towards Christians government officials forced them to adopt surnames containing the Chinese character for “below” or “beneath.”

The wish of the Japanese faithful – “a House of God”

Those who achieved the return to Christianity (Catholicism) were passionately keen to have their own “House of God ” in the communities they lived in, and under the guidance of Bishop Petitjean by the mid-Meiji period churches for the Japanese faithful were constructed in quick succession. Within Nagasaki Prefecture, among others the former Daimyoji Church was built on Io Island between 1879 and 1880; the former Gorin Church on Hisaka Island, one of the Goto Islands in 1881; and the former Ebukuro Church in Shinkamigoto’s Sonego , also on the Goto Islands in 1882. According to the investigations of Hideto Kawakami, a researcher into church architecture, while some of the original churches have been lost due to rebuilding the number of churches constructed in Nagasaki during this period was no less than 30. Father Marie-Augustine Bourelle, Father Joseph Ferdinand Marmand and other priests who were active in Nagasaki in those days exerted themselves in the construction of the churches of the time.

The priests who opened up “a road of love”

Here we will take a look at the priests who devoted all their energies to the early days of the recommencement of missionary work. The anecdotes passed down from one district to another by those who encountered the merciful priests provide us with a glimpse of the times. The first priest we will look at is Father Albert-Charles Pelu, who was ordained in 1870 and entered the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris.

Fr. Pelu arrived in Niigata at the age of 24 in 1872, learned Japanese and started his missionary

work. When he relocated in Nagasaki in 1875, Bishop Petitjean put Fr. Pelu in charge of the running

of a vast parish consisting of Sotome, Kuroshima Island , Hirado Island and Saga Prefecture’s Madara Island. In 1878 He established an “iemido” church within a domestic building in Tasaki, in Hirado Island’s Himosashi District.

Kuroshima Island, off the coast of Sasebo, was an island composed of settlers who moved from Sotome and Hirado during the prohibition of Christianity. Through a visit by Father Jean-Baptiste Poirier in 1872 and subsequent biannual visits by Father Jule Auguste Chatron after the prohibition was lifted, the island became an unusual place in which its entire population became Catholic believers. Fr. Pelu also built the first church on Kuroshima Island. Moreover, he launched the first itinerant missionary ministry in the history of Japan, in which he energetically traveled around a wide area in rowing boats called “kakobune” with local fishermen believers at the oars. In the years following the lifting of the prohibition of Christianity Fr. Pelu made passionate appeals to the Separated Christians to return to Roman Ca tholicism.

Passionately preaching to the Hidden Christians too

The priest who succeeded Fr. Pelu was Father Emile Raguet. After arriving in Nagasaki Fr. Raguet took charge of the Kaminoshima district and Io Island , the latter of which lies outside Nagasaki Harbor, and in 1881 he built a church in Kaminoshima, later using this experience to build another church in 1885 at Himosashi, which he used as the base for his activities. Around this time, because the number of believers on Kuroshima Island was increasing it was predicted that the amount of agricultural land would become insufficient, and a land was purchased in the Tabira district of what is now Hirado City. Three families moved to settle there, and the foundations for the present day Tabira Church were built. Based on the success of this Fr. de Rotz invested his own money to buy large areas of land in both the Tabira and Himosashi districts, and a major project was launched to settle the faithful from Sotome and Shitsu.

Fr. Jean-François Matrat who arrived in Nagasaki in 1881 served as curate to Fr. Raguet, and after taking charge of the wide era of Kuroshima Island and Madara Island eventually took over from Fr. Raguet to become the chief priest of the Hirado district. On Hirado at that time, the former Hidden Christians who settled on the east coast had returned to Catholicism , but those living on the west coast of Hirado and the people of Ikituski Island were still Separated Christians protecting their own former forms of belief. Fr. Matrat passionately preached to the Separated Christians and, for the sake of those who returned to conventional Christianity, built the Kamikozaki Church, Hoki Church and Osashi Church. He also built the Yamada Church on Itsuki Island in 1912.

Deeply moved by the teachings of the priests

Furthermore, Fr. Matrat devoted his energies to the development of the orphanage and the Tasaki Aikukai educational institution (the present day Congregation of Mary of the Annunciation) that had been established by Fr. Pelu in 1878. There, while conducting agriculture and weaving he looked after orphans and elderly people. At the time of construction only 16 households were believers and the members of the Tasaki Aikukai, under the instruction of Fr. Matrat and with the object of helping the elderly and ill in their homes as well as interacting with them, went from door to door as tradesmen loaded with everyday goods and medicines. Initially they were rejected or jeered at, but through their persistence and strength people started to listen to the correct teachings of the Christian Church and some received baptism on their death beds. Fr. Matrat didn’t only lead the Hidden Christians back to the Catholicism; it was not unusual for him to convert the Buddhists in Himosashi to Christianity. Fr. Matrat, who spent his 40 years as a priest entirely on Hirado, loved wearing wooden clogs, humming Japanese elementary school songs and had a childlike side. But he refused to employ women at the priest’s house, could look after himself and was stringent in guiding the faithful, all of which endeared him to his flock.

The recommencement of Christianity in Amakusa started with a single fisherman

The figures who related to Bishop Petitjean the discovery of Hidden Christians in the Amakusa district were the fishermen brothers of Pedro Masakichi Nishi and Miguel Chukichi Nishi, who were the Bishop’s right-hand men in Nagasaki’s Kaminoshima. Sometime around 1874 Masakichi entered a part of Oe Village called Nonaka, and under cover of the night assembled the villagers and told them about Christian stories. Among those listeners were a husband and wife who joined Masakichi on his return to Nagasaki. Tokumatsu Michida left after his wife, but when the couple met Fr. Laucaigne at Oura Cathedral they were so impressed with the sincere response of the priest and the Christian teaching he gave that it was Tokumatsu who asked to be baptized. When Tokumatsu and his wife returned to Oe Village with a missionary it served as the starting point in which signs of a return to Christianity in the village could be seen. In March 1876, Tokumatsu, naming himself “Amakusa Oemura Nonaka, commoner, Tokumatsu Michida” submitted to Kumamoto Prefecture a Petition to Change Religion . In June that year, eight people headed by Tokumatsu filed a Petition of Religious Conversion. In the Amakusa of the early Meiji period abandoning Buddhism or Shintoism and converting to Christianity was a matter of considerable seriousness. Amid this state of affairs, the itinerant missionaries started to visit the island. This was 12 years after the dedication ceremony of Oura Cathedral.

The Christians, trusted by Buddhists

From the perspective of the missionaries the greatest subject of interest was whether or not there were any traces of the propagation of the faith had once been transmitted and what the ancestors of those who were preached to were doing. In 1877 Fr. Marmand arrived in the Amakusa islands. He was followed by Fr. Corre who visited the islands on four occasions and strove to locate the descendants of the Hidden Christians. Two years later Fr. Corre took up the post of priest of Kumamoto Catholic Church (the present day Tetori Catholic Church). The journal of missionary work of the time shows that he traveled around each district meeting with many people. A well as propagating the faith Fr. Corre also devised and executed many projects including the establishment of sanatoriums for Hansen’s disease sufferers in Kumamoto, an orphanage and a school for girls. Subsequently, a permanent settler priest, Father François Bonne, arrived on the islands and recommenced missionary work there. In 1880 Fr. Bonne, who would later be appointed as the third principal of the Nagasaki Catholic Divinity School, took over charge of the Amakusa islands region.

There were descendants of hidden Christians in every village but, fearing persecution, when investigations were made into them they all denied any knowledge of Christianity. However, it is said that Fr. Bonne sometimes rushed at night to the bedside of those near death in order fulfill the wishes of the sick who wanted to be baptized. Meanwhile, no persecution of the Christians took place in the villages, and quite to the contrary they were so trusted that when arguments or conflict broke out they were often selected to serve a mediators. The headman of Oe Village hoped that all of the villagers would become Christians, and towards the end of the 19th century the headman of Sakitsu Village, where 550 of the 600 households were former Hidden Christians , provided land and financial donations with the wish that a church would be built there as soon as possible, although he himself followed another faith.

The spirit of welfare taught by the priests

The second priest to settle was Father Joseph Ferrié, who served for seven years and interacted with the descendants of Christians in various places. After having served for two years the number of the faithful had increased to 142 in Oe, 244 in Sakitsu, and 67 in Imatomi, a total of 453 people. Fr. Ferrié started the construction of Oe Church in 1883 and of Sakitsu Church the next year. Furthermore, he stretched out a helping hand to the children who were so poor and starving to eat that they poached food from people’s fields, and established the Nebikinokobeya Orphanage deep in the mountains at a location now around a 30-minute drive by car from Sakitsu Church. At the orphanage he brought food from the church and along with the children cleared the area and cultivated fields, teaching the children the skills of being self-sufficient. Fr. Ferrié’s successor, Father Fredric Louis Garnier visited this orphanage every week and ensured that the children could look after themselves. When the children grew up they were fostered to other families or worked as baby sitters, and were rounded into independent people.

The way of life that Fr. de Rotz taught in the Sotome region

After taking up his new post in the Sotome region in 1879, the first thing that Fr. de Rotz did was to establish a girls’ boarding school. Five young women including Shige Oishi lived in a group and spent their days learning techniques such as weaving and dyeing. The Shitsu boarding school was named the Congregation of St. Joseph Convent, and in 1883 the Shitsu Aid Center Workshop was established on the site of the former village headman’s compound. Widows of men who had died at sea and the daughters of poverty-stricken farmers equipped themselves here with skills such weaving, sewing and milling; they were also given instructions in elementary reading, writing and calculation. Later on instruction was also provided in the making of bread, macaroni and somen noodles, as well as oil pressing. These were all skills that Fr. de Rotz himself was equipped with, and did not hesitate to teach others about.

Not all the women who learned and worked at the Aid Center Workshop went on to devote their lives as nuns. After leaving the Workshop they were free to do as they pleased, and many of them now equipped with techniques and education became housewives. Fr. de Rotz set “creating good mothers” as one of his goals, and the Workshop thereby also acted as a finishing school. In addition, Father de Rotz obtained agricultural tools and excellent varieties of wheat and so on from France, and taught the men how to clear wastelands, improve farming, and guided them in French agricultural techniques.

The visitor to present day Sotome will find that even 140 years after his time there the local people sill refer to him fondly with the honorific suffix of “sama,” and understand why his presence still resonates throughout this area.

COLUMN3 Shitsu Aid Center Workshop

◆The former Shitsu Aid Center Workshop

The Workshop is a group of buildings erected in order to conduct industry training activities for the assistance of the people of poverty-stricken Sotome. In the training building at its heart local people conducted spinning and weaving from cotton materials, dyeing, the production of somen noodles and bread, and the fermentation of soy sauce. The macaroni factory equipped with machinery shipped in from the West, and its “de Rotz walls” devised by Fr. de Rotz using irregularly placed local stones are both National Important Cultural Properties. The production of fishing nets started with the cultivation of the hemp that was their raw material, and the oil required for somen noodle and macaroni production was obtained by pressing peanuts cultivated by the Workshop. Everything was conducted according to Fr. de Rotz’s formula, from the production of raw materials through to the finished product. The bread and macaroni were sold to foreign residents in Nagasaki like Thomas Blake Glover. They visited Shitsu by boat on many occasions.

The father of the Discovery of the Hidden Christians, opened up the path for the recommencement of missionary work and then passed away

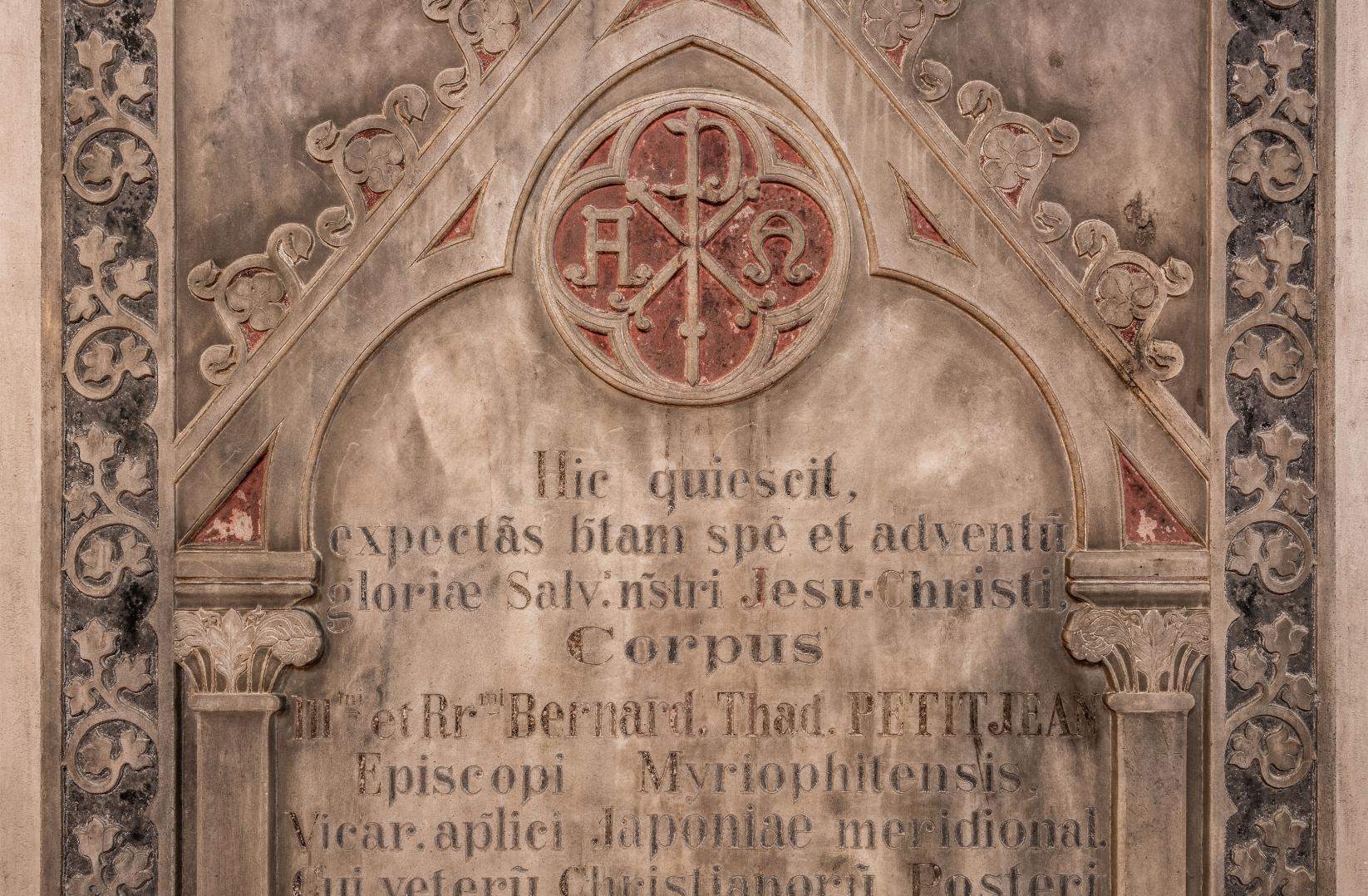

Starting with the construction of Oura church, the Discovery of the Hidden Christians, then the Fourth Urakami Crackdown, banishment of entire communities, the abolition of the bulletin boards banning Christianity, recommencement of missionary work, fostering of Japanese priests and the start of building churches – all this during the 21 years since he arrived in Japan. Bishop Petitjean, who had truly lived through years of the utmost turbulence, finally passed away on October 7 1884 due to pleurisy and coronary complications. He was 55 years old.

If you proceed up the nave of Oura Cathedral towards the main altar, on the righthand wall there is a soapstone epitaph that is the tombstone of Bishop Petijean. This is said to be the spot where Bishop Petijean knelt and said a prayer when Yuri Isabelina Sugimoto first spoke to him. His body was, as he had wished, buried under the cathedral floor just before the altar steps , and his presence is still a part of Oura Cathedral today.

COLUMN4 The tombstone of Bishop Petitjean

◆The tombstone of Bishop Petitjean

If you proceed up the nave of Oura Cathedral towards the main altar, you will notice that on the righthand wall there is a large plaque with an epitaph on it. This is the tombstone of Bishop Petijean, the father figure of the Hidden Christians, the man who was responsible for promoting theological education for the Japanese believers who returned to Catholicism, and made a huge contribution to the recommencement of missionary work. His remains rest just below the steps to the main altar. As the Christian tradition includes praying to the dead and sacred relics, tombs have long been placed near church and cathedral altars, and the soapstone plaque epitaph is engraved in both Latin and Chinese characters. In 2024, the 130th anniversary of his death, the great missionary Bishop Petitjean was celebrated with memorial masses and other ceremonies.

Component

SHARE

NEXT